The Crow—Alex Proyas’s 1994 cult film about a man brought back from the dead to avenge the murder of his fiancée—was marred by tragedy when its star, Brandon Lee, was killed in an on-set accident just days before the film was scheduled to wrap, and not long before he was to be married. Here are a few things you might not have known about the film. (Warning: Violence and profanity in some of the videos below.)

1. The Crow is based on a comic book, which was inspired by two tragedies.

In 1981, 21-year-old James O’Barr was drawing combat manuals in the Marines when he decided to start The Crow. He hoped it would be a healthy way of dealing with the death of his fiancée, who had been killed by a drunk driver. “I tried all the typical angst-ridden outlets, like substance abuse and going to clubs or parties every night and just basically trying to keep yourself numb for as long a period of time as possible,” O’Barr told The Baltimore Sun in 1994. “Eventually I was smart enough to realize that that was a dead end, and so I thought perhaps putting something down on paper I could exorcise some of that anger.”

Pivotal to his comic book’s plotline was another tragedy O’Barr heard about: A couple killed over an engagement ring. “I thought it was outlandish, a $30 ring, two lives wasted,” he said in a book about the production called The Crow: The Movie. “That became the beginning of the focal point, and the idea that there could be a love so strong that it could transcend death, that it could refuse death, and this soul would not rest until it could set things right.”

2. There was interest in turning the comic book into a movie early on.

The Crow comic book debuted on February 1, 1989. Shortly after the second issue came out, O’Barr—who at that time was doing auto body work—was approached by a young director who was interested in buying the rights to The Crow for a one-time lump sum. “All rights, all media, in perpetuity,” O’Barr said in The Crow: The Movie, “but the money was pretty good, considering. I was going to do it.” But his friends convinced him to consult with a Hollywood agent, who advised O’Barr against selling the rights to the comics for a lump sum.

Then, right when the third issue was coming out, O’Barr met writer John Shirley and producer Jeff Most, who were eager to adapt the book into a movie. “Their enthusiasm convinced me that the film would be done correctly,” O’Barr said. “Even though it was for far less than what I had previously been offered, I wasn’t selling out my copyright, and it was the best chance of the film turning out to be something I’d want to see. I just went with my instincts.”

3. Writer John Shirley and producer Jeff Most made some changes to O’Barr’s antihero.

Shirley and Most got to work right away adapting The Crow into a script. They made a few changes, downplaying Eric’s drug use and bringing the love story to the fore. They also made the crow an actual animal—not just Eric’s psyche, as it is in the comics—that spoke to Eric telepathically.

While Shirley worked on the script, Most took the treatment and the comics and went about shopping the screenplay. Eventually, independent producer Ed Pressman signed on to help make the movie, and for the next two years, Shirley honed the script. He added an older brother for Sarah (a version of a character from the comics), a young girl with a drug addict for a mother who befriends Eric and Shelly, and turned the Skull Cowboy, a manifestation of Eric’s mental anguish that appears three times in the comics, into a guide.

Eventually, O’Barr thought the creative team had gone too far with their changes, so he created a 10-page outline explaining his characters’ motivations to get them back on track. Not long after, horror writer David J. Schow (Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III and Critters 3 and 4) came onboard to do a rewrite; he told Pressman that Eric Draven should be a “Gothic, rock and roll Terminator.” Schow cut back on the number of villains, gave the remaining ones a clear hierarchy, and added Devil’s Night as the motivating factor behind the initial attack on Eric and Shelly, “just to give the villains a more esoteric agenda,” he said in The Crow: The Movie. Making that decision also grounded the movie in Detroit, a city that regularly experienced fires and mayhem the night before Halloween.

4. The producers knew who they wanted to direct and star.

Pressman had Alex Proyas, an Australian director who at that point had helmed music videos and commercials, but no features, in mind to direct The Crow. Though Proyas was very much in demand in Hollywood, he was waiting for the right project—and The Crow was it. He signed on in 1991.

The producers first looked at musicians to fill the role of Eric Draven, among them Charlie Sexton, a rocker from Texas. But ultimately, their first choice was Brandon Lee. At that point, Lee—son of famed actor/martial artist Bruce Lee—had appeared in a few films, but hadn’t had a breakout role yet. “We had considered some more established actors and we were concerned that certain of these actors did not have the athletic ability,” Pressman said in The Crow: The Movie. “Other people had the athletic ability but not the acting talents. Brandon combined it all. When Brandon walked into this office, it was an immediate flash. We knew we had our Eric Draven that instant.”

5. Brandon Lee asked for one character to be removed.

Once Lee signed on to star in The Crow, he read the comic book. “After the script was written, Alex [Proyas] and I went back to the comic book and tried to find the beats of the story that didn’t make it into the script,” Lee said at one point during production. Proyas took Lee’s feedback seriously, and often incorporated his changes into the script. That included cutting one super-villain, an Asian character out to steal Eric’s powers, whom Lee thought was a stereotype.

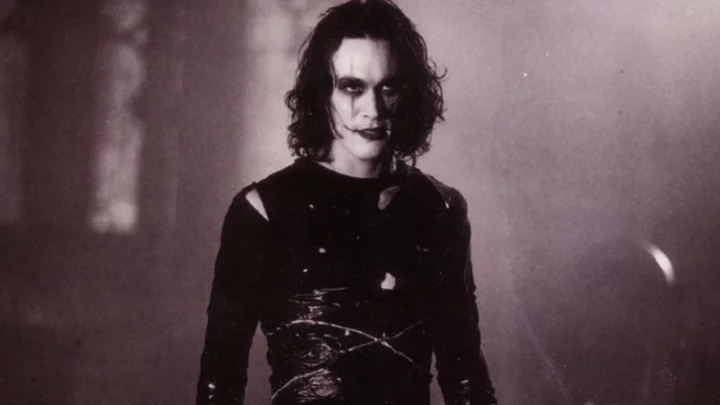

6. It was tough to get the makeup right.

There’s a persistent rumor that Eric Draven’s makeup was inspired by Alice Cooper or KISS—and it’s a rumor that O'Barr denies. At a comics convention in 2009, O’Barr said that The Crow’s look came from a marionette mask, which he saw painted on a theater in London: “I thought it’d be interesting to have this painful face with a smile forcibly drawn on.”

Regardless of what inspired the makeup, getting it right was very tough. It took between 35 minutes and an hour to apply the grease makeup, which could stay in place for hours; special effects artist Lance Anderson created a rubber mask that had slits in it, so that the pattern of lines around the eyes and mouth would be consistent.

But Proyas and Lee weren’t fans of the freshly applied look. “The first few times Brandon and I looked at it we were both really unhappy with it,” Proyas admitted in the DVD commentary. “It was hard to get it to the point where it didn’t feel self-conscious. We were both happy with it when it was distressed—he almost wanted to sleep in the makeup and then come to set the next day. That’s when it would look really great.”

7. David Patrick Kelly bought a vintage copy of Paradise Lost for the production.

Some of the actors cast as villains in The Crow went through training to portray their characters; Laurence Mason, for example, worked with stunt coordinator Jeff Imada to learn real-life knife-fighting moves in order to play Tin Tin. Others donned costumes: Michael Massee, who played Funboy, wore outfits inspired by Iggy Pop and some outfits taken directly from the comic. David Patrick Kelly, who played T-Bird, used a more literary inspiration to get into character: John Milton’s Paradise Lost. T-Bird quotes Milton in the flashback sequences; Kelly bought an antique copy of the book to use in the scene.

8. They used ravens, not crows, during filming.

Animal trainer Larry Madrid trained five ravens for the production. Because The Crow filmed at night—when ravens sleep—he had to get the birds accustomed to that, as well as flying in the rain (which is also unnatural for the birds) and in a wind tunnel. One of the ravens also had to be trained to be comfortable sitting on Lee’s shoulder.

9. The production employed plenty of tricks to get its shots.

The Crow didn’t have a huge budget, so the filmmakers sometimes relied on trickery to get the shots they needed. For the opening sequence, which shows a city on fire, the production used miniatures and projection technology. “We went to elaborate lengths to project flames into a miniature set,” Proyas said in the DVD commentary. “We had a screen set up so we could project into the miniature on multiple passes. It was really the very early days of digital imagery, and we didn’t really have the money to use them, so we tried to do things in much more of an optical way.”

For one iconic shot in which Eric dumps a bunch of rings into the barrel of a shotgun and fires it, Proyas “cut to some oversized rings being dropped towards the camera through a puff of smoke,” he said. “The way it’s cut, you really think you’re seeing a bunch of rings that were dropped into a shotgun.” The production didn’t have the money—or the space—to shoot a car chase sequence, so they did it with miniatures instead. And the final rooftop confrontation between Eric and head-villain Top Dollar (Michael Wincott) was shot not on the roof of a church, but on modular pieces sitting on the soundstage floor that were made to look like a gothic cathedral.

10. They used special effects, too.

For a scene in which the crow attacks Myca (Bai Ling), Anderson built a mechanical bird to do the attacking; it had separate controls for the wings and the claws. His shop also built mechanical hands that looked just like Lee’s for a scene in which Eric is shot in the hand and his hand heals. “What we ended up doing,” Anderson said in The Crow: The Movie, “was closing it to a point and then taking filler and filling the hole in so it would close totally clean and go away, like stop motion.” They also created a full dummy of Top Dollar to be used in the climactic fight sequence where he’s impaled on the horn of a gargoyle.

11. James O’Barr makes a cameo in The Crow.

He’s the looter who steals a television in the aftermath of the explosion at Gideon’s Pawn Shop.

12. With just a few days left to film, Lee was killed in a tragic on-set accident.

The cast and crew worked long, grueling hours, in the rain and at night, on the set of The Crow, which was plagued by misfortunes almost from the start. In February 1993, a carpenter was seriously injured on set when the crane he was working in hit live power lines. That night, an equipment truck caught on fire. Later, a sculptor who had worked on the set for just a few days drove through the plaster shop after he was let go. A construction worker accidentally drove a screwdriver through his hand. Then, in March, a storm destroyed some of the sets.

On March 31, 1993, the production was filming a flashback sequence that showed how Eric died: As he walked into the apartment he shared with Shelly to find her being raped and beaten by Top Dollar’s henchmen, Funboy would pull out his .44 Magnum and shoot him. According to People:

“The script of The Crow called for a close-up of the loaded weapon. The crew, following standard procedure, used dummy bullets, which are nothing more than bullets without gunpowder. When the close-up was finished, the gun was unloaded, then reloaded with blanks. Blanks sound as loud as real bullets, but when they are fired, only the harmless cardboard wadding with which they are packed is ejected from the gun. This time, though, the action was far from benign. Massee pulled the trigger, and Lee slumped to the ground, a hole the size of a quarter in his lower right abdomen.”

The crew didn’t realize that Lee was injured until Proyas called cut and the actor didn’t get up. He was rushed to the hospital, but doctors couldn’t save him. Lee died later that afternoon; he was just 28 years old.

It took some time to figure out what had happened, but according to The Telegraph, both the dummy bullets and the blanks used on the production “had hastily been fabricated by taking out the gunpowder from real bullets because of the time pressure crew members were under.” The lead tip of the dummy bullet became lodged in the barrel of the gun and, “pushed out by the blank charge, scratched the bottom of the shopping bag before perforating Lee’s navel, and managed to puncture the stem of the aorta where it branches to provide blood supply to the legs.”

After the accident, Paramount—which had agreed to distribute the movie—dropped out, leaving the film in limbo (Miramax eventually picked it up). Producers, with permission from Lee’s family, wanted to finish the film, and after a six-week bereavement period, the cast and crew returned to Wilmington to complete filming The Crow.

No criminal charges were ever filed in Lee’s death, but his mother, Linda Lee Cadwell, did file a lawsuit against the producers and production company, which was eventually settled. In 2005, Massee spoke out about the accident for the first time. “It absolutely wasn’t supposed to happen. I wasn’t even supposed to be handling the gun until we started shooting the scene and the director changed it,” he said. Afterward, “I just took a year off and I went back to New York and didn’t do anything. I didn’t work. What happened to Brandon was a tragic accident ... I don’t think you ever get over something like that.”

13. After Lee’s death, the script was reworked—and one character was cut.

One month after Lee's death, Pressman and Proyas began rewriting the script, ultimately presenting, according to Entertainment Weekly, “an emotionally softened, reworked script.” The filmmakers opted to use Lee’s half-finished scenes in montages, and they cut one character altogether: the Skull Cowboy, played by Michael Berryman, a guide who laid out the rules of Eric’s return to the land of the living. According to The Crow: The Movie, those rules were “ice the bad guys, receive a reunion with Shelly—but ‘work for the living, you bleed.’”

In the DVD commentary, Proyas said he cut the character for a number of reasons. “I was never happy with the effect … I felt he lowered the standard of the film, made it a little cheesy,” he said. “But also because I felt that the character was kind of unnecessary. I feel that you get what’s going on, you understand it, you don’t really need someone telling you, as an audience, what’s happening at various points, and that seemed to be the function that he was playing. We [also] only got to shoot one scene with him, and there were two other scenes planned that we didn’t get to shoot. How do you make more of him without Brandon to relate to him, and why would you even want to bother? It was an easy decision to drop him.”

The Skull Cowboy’s exposition was replaced with Sarah’s narration, and Eric only becomes mortal when the crow he’s been following is killed.

Other scenes that ended up on the cutting room floor involved Skank (Angel David) being robbed by children and an extended fight sequence between Eric and Funboy in which Funboy actually wounds Eric. Proyas said on the DVD that they cut the fight for two reasons: One, because now that the Skull Cowboy was gone, the conceit that Eric doing something for the living would make him vulnerable wasn’t clear, and also because “we had so little time to shoot the fight scene that Brandon and I, neither of us were particularly happy with the results,” Proyas said. “He had choreographed a really beautiful sequence, and I really hadn’t been able to capture it in the time we had.”

Thanks to the changes, “In a way, the film became about something different,” one source told Entertainment Weekly. “It became about how you deal with grief. What happens when someone you love is taken from you? How do you incorporate that into your life?”

14. Cutting-edge visual effects were used to complete the film after Lee’s death.

In addition to having doubles stand in for Lee, and filming those scenes as long shots in shadows, the production relied on the VFX company Dream Quest Images to fill in some of the blanks. Using footage of Lee from other sequences, the visual effects company finished seven shots. In one sequence where Eric enters his abandoned loft, Dream Quest took a shot of Lee stumbling down an alley and digitally removed the background; by adding a matte painting of a doorway, they were able to make it look like he was actually walking into his apartment. In another shot where Eric sees himself in a broken mirror, Dream Quest once again digitally isolated Lee from an outside shot. Using a shot of a double in front of a shattered mirror as a guide, they were able to create a grid that allowed them to composite Lee’s image onto the mirror (you can see how they did it here). Even more extraordinary, the company did this on handheld footage—a far cry from most visual effects shots at the time, which were carefully planned and staged and shot with a steady camera (just-developed image-tracking software helped them pull it off).

15. Executives were worried that audiences wouldn’t get the movie.

“In the very first test screenings we had, two or three people out of 300 would ask, ‘Why is it that Eric Draven is the guy that can come back with these powers? Why can he come back from the dead?” Proyas recalled in DVD commentary. “I’m going, ‘Who the hell cares ...’ I remember this was a really big thing for everyone at that time, but now, see the movie, it’s obviously ludicrous. It’s a suspension of disbelief, and people go with it.”

16. The Crow was a hit.

The Crow was released on May 13, 1994, and was the number one movie in America in its first weekend. Critics, including Roger Ebert and Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers, praised the movie. Its total domestic gross was nearly $51 million.

17. O’Barr donated most of his profits from the film to charity.

O’Barr bought his mom a car, and a surround sound system for himself, then donated the rest. “I was really good friends with Brandon, so it just felt like blood money to me,” he said at a comics convention in 2009. “I didn’t want to profit at his expense. And I kept that secret for as long as I could. It’s not charity if you get credit for it.”

18. The Crow spawned several sequels.

“It wasn’t utmost in my [mind] to create a franchise, but I was aware that it could do that, and you don’t want to make that impossible,” Proyas said in the DVD commentary. “You can see all the elements there. If Eric Draven was going to come back again, there had to be some layers to it, there had to be some reason for him to come back ... I would have been delighted to make The Crow 2, and if Brandon had been involved, we would have made a great movie.”

Even without Lee, though, the sequels came. The Crow: City of Angels, starring Mia Kirshner as Sarah and Vincent Perez as The Crow, Ashe Corven, was released in 1996. In 1998, there was a short-lived TV series called The Crow: Stairway to Heaven starring Mark Dacascos. Then, in 2000, Kirsten Dunst and Eric Mabius starred in another movie, The Crow: Salvation. That was followed in 2005 by The Crow: Wicked Prayer, which starred Tara Reid, David Boreanaz, and Edward Furlong.

19. A reboot of The Crow is coming in 2024.

Talk of a reboot of The Crow has been percolating since 2008. The movie lost several stars and directors, and weathered a production company’s bankruptcy, but news recently hit that the movie—directed by Rupert Sanders and starring Bill Skarsgård, FKA Twigs, and Danny Huston—was acquired by Lionsgate, which is planning a 2024 release. “We appreciate what The Crow character and original movie mean to legions of fans,” a Lionsgate executive said, “and believe this new film will offer audiences an authentic and visceral reinterpretation of its emotional power and mythology.”

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2023.

This article was originally published on www.mentalfloss.com as 19 Fascinating Facts About ‘The Crow’.